What is a Labyrinth?

A labyrinth is a meandering path, usually unicursal, with a singular path leading to a centre. Unlike a maze it is impossible to get lost if following the path. Labyrinths are an ancient archetype dating back 4,000 years or more, used symbolically, as a walking meditation, choreographed dance, or site of rituals and ceremony, among other things. Labyrinths are tools for personal, psychological and spiritual transformation, also thought to enhance right-brain activity. Labyrinths evoke metaphor, sacred geometry, spiritual pilgrimage, religious practice, mindfulness, environmental art, and community building.

It is generally thought that their popularity in the Middle Ages, at the time of the Crusades, was because there were so many people who were unable take on a pilgrimage to one of the holy places – Rome, Jerusalem, etc – and the labyrinth meant that they could take a local prayerful journey, which is why so many are in churches or on holy ground. The journey through the labyrinth is not straightforward and the walker can at times seem to be walking away from the centre, mirroring experiences in life.

Labyrinths are named by type and can be further identified by their number of circuits. You begin a labyrinth walk at the entrance and proceed along the path. Lines define the path and often maintain a consistent width, even around the turns. Generally, at the centre you have travelled half the distance, where it is common to pause, turn around, and walk back out again.

Who is this for?

This can be done individually or as a group. This can be guided or self-guided.

Method:

There are many ways to use a labyrinth (see the books available) but the most common is to use the way to the centre to focus in on any issues or questions you may have, or see what comes up; then in the centre to wait on God and listen for God’s word. On the way back out, you can then ponder of God’s word to you and this time and what challenges or comfort it brings.

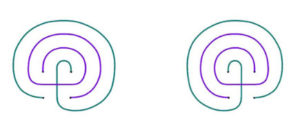

Labyrinths can be of any size and in many forms. The Cretan and Chartres forms are illustrated here:

Scenic canvas painted with acrylic paint forms a good serviceable portable labyrinth. They can also be mown into a lawn or laid out with stones in a garden. On the beach, stones can be used, or the labyrinth can be drawn on the sand with a stick. Ropes can also be used in a hall to create another form of temporary labyrinth.

There are maps of where to find labyrinths in various books and on the internet, labyrinthlocator.org

Small labyrinths can be printed or drawn, or – more permanently – created in felt or fabric or clay. The path is then ‘walked’ with a finger, though the prayer format remains the same.

Instructions for drawing a Cretan labyrinth or for creating one with two ropes can be found here.

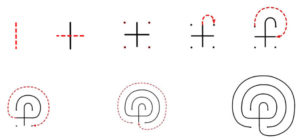

Step by Step to Lay Out a Three-Circuit Classical Labyrinth

When practicing on paper, place the first two steps in the center of your page leaving room for the extra circuits that are to come. At step 4 if you move to the right, you will have a left turning labyrinth, if you move to the left, a right turning labyrinth.

Three-Circuit Labyrinth From Two Pieces of Rope

Colour the outer line of the labyrinth one colour and the other line a second colour.

Then choose two pieces of coloured rope to create your labyrinth, making sure that your outer rope is the longer piece.

Walkable: Outside, long rope: 27 feet (823 cm) Inside, short rope: 24 feet (732 cm)

These ropes make an approximate 3-circuit labyrinth that is 7-feet (213 cm) in diameter and can be modified to fit any shape or made smaller.

Tabletop: Outside, long rope: 61 inches (155 cm): Inside, short rope: 51 inches (130 cm):

These ropes make an approximate 3-circuit labyrinth that is 18 inches (46 cm) in diameter.

(Assembly instructions: Lea Goode-Harris, Ph.D. leagoodeharris.com)